Last Year's Snow: The Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde in the 1970s & 80s

9th October 2015 - 13th November 2015

Austin / Desmond Fine Art is delighted to announce an exhibition of works by the Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde in the first show of its kind to be held in London. Artists exhibited will include Gábor Attalai, Miklós Erdély, Tibor Hajas, György Jovánovics, Katalin Ladik, Dóra Maurer, Géza Perneczky, Endre Tót, Bálint Szombathy and Tamás Szentjóby.

In the post-war period Hungary suffered under the dictatorship of the Soviet Union whose ideology at the time was hostile to modern art. The authorities established the official art form of ‘Socialist Realism’, as representation of the achievements of the great socialist era. Parallel to this, Hungary’s artists were establishing what became known as the un-official art scene, working outside of the highly censored institutional system. This un-official scene often operated underground, using private apartments as show spaces and holding clandestine semi-illegal exhibitions. Their ‘isolation’ led to a flourishing alternative cultural milieu in which artists worked in intense interaction with each other regardless of the use of medium or artistic references.

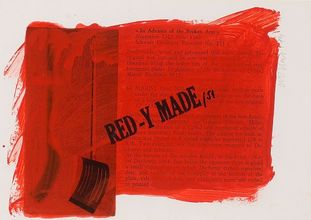

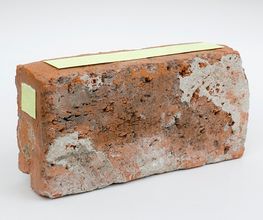

Included in the exhibition at Austin / Desmond Fine Art will be works by ten of the leading protagonists of this movement. Miklós Erdély, one of the most important catalysts of the Hungarian un-official art scene and whose work Last Year’s Snow (1970)the exhibition title is taken from, will be exhibited alongside his renowned contemporary Tamás Szentjóby. Both artists reflect on the political and social issues of the time in a critical yet ironic way. St.Auby’s Fluxus objects include the Czechoslovak Radio (1968), an example of which was exhibited at Documenta in 2011: a simple painted brick alludes to the 1968 suppression of Czechoslovakia’s new reforms (Prague Spring) when citizens were banned from using radios and took to the streets with paper covered bricks in protest.

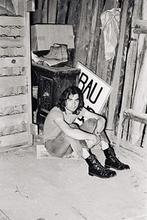

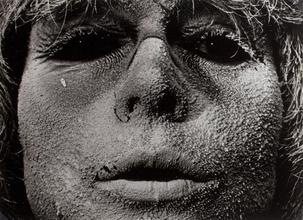

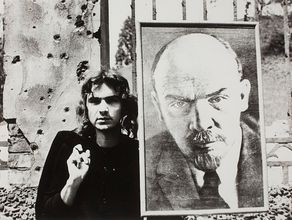

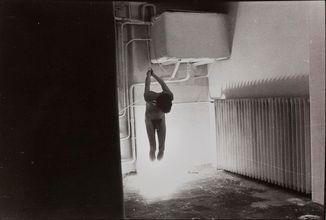

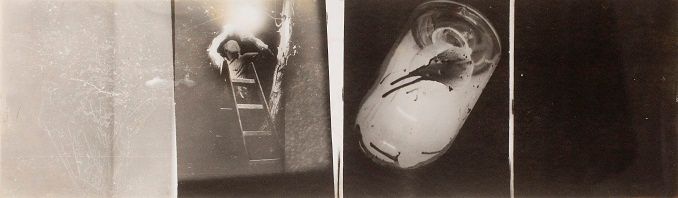

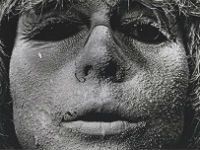

Also featured are the conceptual works of Gábor Attalai and Géza Perneczky alongside the photo-performance series by Bálint Szombathy, Katalin Ladik and Tibor Hajas. Using their bodies as the medium, these artists performed intimate events without audiences, often with a subversive or political overtone. Exhibited will be Szombathy’s iconic and rebellious work Bauhaus (1972/2013) performed in the attic he was renting in Novi Sad. The work portrays the humerous juxtaposition between his grim living conditions and his caustic political placards depicting the word BAUHAUS.

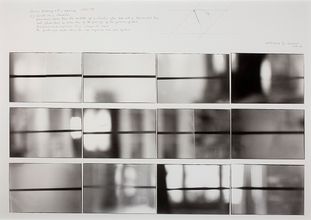

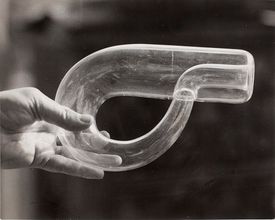

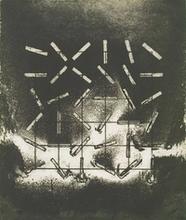

The unusual combination of neo-constructivism and conceptual art is best embodied in the works of Dóra Maurer and György Jovánovics. Included in the exhibition will be the work Sluices No. 9 (1980) by Maurer, an example of her experimental print making which also demonstrates her interest in the rigour of geometric abstraction. Maurer, whose work has finally received the deserved attention of the international art world was included in the recent exhibition Adventures of the Black Square at the Whitechapel Gallery, London and her 2014/2015 retrospective at Museum Ritter has highlighted the diversity of her highly regarded oeuvre.

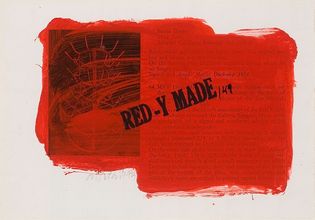

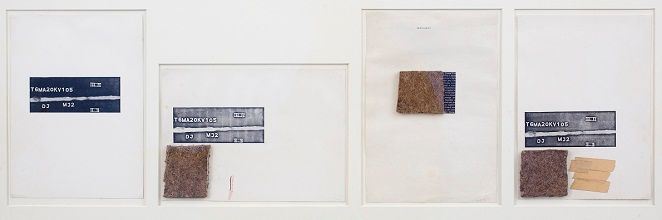

Endre Tót, a key practitioner of Mail art, camouflaged his art in letterform in order to avoid the postal censorship of the time. Mail art was used as a common practice amongst the Eastern Bloc artists to disseminate their works and communicate with each other and their Western counterparts. In his series Zeropost, (1976) Tót mailed his letters with his Zero stamps as reflections of the absurdity of communication in a dictatorship. Ironically, despite the non-official postage, the letters still arrived at their destinations.

“Sending out a stamp, a letter or a card, something that in the west carried no risk and involved no emotional investment, was connected in the East with a defence of the basic human right to free expression and was often understood as a form of public service or protest.”[1]

As the art historian Piotr Piotrowski notes above, the context in which these works were made is crucial to their understanding. Hence whilst the artists behind the iron curtain were following current debates on contemporary art, they were not mimicking their achievements but only using Western practices as a point of reference. The members of the Hungarian unofficial art scene were keen to break the conventions of concrete art, fluxus, conceptual art and even pop art, as established in the West, by combining them in their unique visual language. What evolved was a radical new approach to conceptualism, underpinned by a highly political reaction to the denial of freedom in the practice of art.

Over the past three decades many exhibitions have explored and contextualised the neglected art movements of Eastern Europe. Among these shows, the following musems gave special attention to the Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde: Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s-1980s (1999, Queens Museum, New York), Aspekte/Positionen. 50 Jahre Kunst aus Mitteleuropa, 1949-1999 (1999, MUMOK, Vienna), and the Subversive Practices. Art under Conditions of Political Repression 60s–80s / South America / Europe (2009, Kunstverein, Stuttgart). Concurrently, both private and public collections began to acquire the works of these artists, including the Art Institute of Chicago, Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and Tate, London. In Vienna the Kontakt collection of the Erste Bank is dedicated solely to the post-war conceptual art scene of Eastern Europe

Special thanks to László Beke, Orsolya Hegedus, Gábor Pados, Attila Pocze, Margit Valkó & Artpool Art Research Center.

[1] Piotr Piotrowsky, In the Shadow of Yalta. Art and the Avant Garde in Eastern Europe 1945-1989 (London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2009)

Austin / Desmond Fine Art is delighted to announce an exhibition of works by the Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde in the first show of its kind to be held in London. Artists exhibited willinclude Gábor Attalai, Miklós Erdély, Tibor Hajas, György Jovánovics, Katalin Ladik, DóraMaurer, Géza Perneczky, Endre Tót, Bálint Szombathy and Tamás Szentjóby.

In the post-war period Hungary suffered under the dictatorship of the Soviet Union whose ideology at the time was hostile to modern art. The authorities established the official art form of ‘Socialist Realism’, as representation of the achievements of the great socialist era. Parallel to this, Hungary’s artists were establishing what became known as the un-official art scene, working outside of the highly censored institutional system. This un-official scene often operated underground, using private apartments as show spaces and holding clandestine semi-illegal exhibitions. Their ‘isolation’ led to a flourishingalternative cultural milieu in which artists worked in intense interaction with each other regardless of the use of medium or artistic references.

Included in the exhibition at Austin / Desmond Fine Art will be works by nine of the leading protagonists of this movement. Miklós Erdély, one of the most important catalysts of the Hungarian un-official art scene and whosework Last Year’s Snow (1970)the exhibition title is taken from, will be exhibited alongside his renowned contemporary Tamás Szentjóby. Both artists reflect on the political and social issues of the time in a critical yet ironic way.St.Auby’s Fluxus objects include the Czechoslovak Radio (1968), an example of which was exhibitedatDocumenta in 2011: a simple painted brick alludes to the 1968 suppression of Czechoslovakia’s new reforms (Prague Spring) whencitizens were banned from using radiosandtook to the streets with paper covered bricks in protest.

Also featured are the conceptual works of Gábor Attalai and Géza Perneczky alongside the photo-performance series by Bálint Szombathy, Katalin Ladik and Tibor Hajas. Using their bodies as the medium, these artists performed intimate events without audiences, often with a subversive or political overtone. Exhibited will be Szombathy’s iconic and rebellious work Bauhaus (1972/2013) performed in theattic he was renting in Novi Sad. The work portrays the humerous juxtaposition between his grim living conditions and his caustic political placards depicting the word BAUHAUS.

The unusual combination of neo-constructivism and conceptual art is best embodied in the works of Dóra Maurer and György Jovánovics. Included in the exhibition will be the workSluices No. 9 (1980) by Maurer, an example of herexperimental print making which also demonstrates her interest in the rigour of geometric abstraction. Maurer, whose work has finally received the deserved attentionofthe international art world was included in therecentexhibition Adventures of the Black Square at the Whitechapel Gallery, London and her 2014/2015 retrospective at Museum Ritter has highlighted the diversity of her highly regarded oeuvre.

Endre Tót, a key practitioner of Mail art, camouflaged his art in letterform in order to avoid the postal censorship of the time. Mail art was used as a common practice amongst the Eastern Bloc artists to disseminate their works and communicate with each other and their Western counterparts. In his series Zeropost, (1976) Tót mailed his letters with his Zero stamps as reflections of the absurdity of communication in a dictatorship. Ironically, despite the non-official postage, the letters still arrived at their destinations.

“Sending out a stamp, a letter or a card, something that in the west carried no risk and involved no emotional investment, was connected in the East with a defence of the basic human right to free expression and was often understood as a form of public service or protest.”[1]

As the art historian Piotr Piotrowski notes above, the context in which these works were made is crucial to their understanding. Hence whilst the artists behind the iron curtain were following current debates on contemporary art, they were not mimicking their achievements but only using Western practices as a point of reference. The members of the Hungarian unofficial art scene were keen to break the conventions of concrete art, fluxus, conceptual art and even pop art, as established in the West, by combining them in their unique visual language. What evolved was a radical new approach to conceptualism, underpinned by a highly political reaction to the denial of freedom in the practice of art.

Over the past three decades manyexhibitions haveexploredand contextualised the neglected art movements of Eastern Europe. Among these shows, the following musems gave special attention to the Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde: Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s-1980s (1999, Queens Museum, New York), Aspekte/Positionen. 50 Jahre Kunst aus Mitteleuropa, 1949-1999 (1999, MUMOK, Vienna), and the Subversive Practices. Art under Conditions of Political Repression 60s–80s / South America / Europe (2009, Kunstverein, Stuttgart).Concurrently, both private and public collections began to acquire the works of these artists, including the Art Institute of Chicago, Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and Tate, London. In Vienna the Kontakt collection of the Erste Bank is dedicated solely to the post-war conceptual art scene of Eastern Europe

[1]Piotr Piotrowsky, In the Shadow of Yalta. Art and the Avant Garde in Eastern Europe 1945-1989 (London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2009)

Austin / Desmond Fine Art is delighted to announce an exhibition of works by the Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde in the first show of its kind to be held in London. Artists exhibited will include Gábor Attalai, Miklós Erdély, Tibor Hajas, György Jovánovics, Katalin Ladik, Dóra Maurer, Géza Perneczky, Endre Tót, Bálint Szombathy and Tamás Szentjóby.

In the post-war period Hungary suffered under the dictatorship of the Soviet Union whose ideology at the time was hostile to modern art. The authorities established the official art form of ‘Socialist Realism’, as representation of the achievements of the great socialist era. Parallel to this, Hungary’s artists were establishing what became known as the un-official art scene, working outside of the highly censored institutional system. This un-official scene often operated underground, using private apartments as show spaces and holding clandestine semi-illegal exhibitions. Their ‘isolation’ led to a flourishing alternative cultural milieu in which artists worked in intense interaction with each other regardless of the use of medium or artistic references.

Included in the exhibition at Austin / Desmond Fine Art will be works by nine of the leading protagonists of this movement. Miklós Erdély, one of the most important catalysts of the Hungarian un-official art scene and whose work Last Year’s Snow (1970)the exhibition title is taken from, will be exhibited alongside his renowned contemporary Tamás Szentjóby. Both artists reflect on the political and social issues of the time in a critical yet ironic way. St.Auby’s Fluxus objects include the Czechoslovak Radio (1968), an example of which was exhibited at Documenta in 2011: a simple painted brick alludes to the 1968 suppression of Czechoslovakia’s new reforms (Prague Spring) when citizens were banned from using radios and took to the streets with paper covered bricks in protest.

Also featured are the conceptual works of Gábor Attalai and Géza Perneczky alongside the photo-performance series by Bálint Szombathy, Katalin Ladik and Tibor Hajas. Using their bodies as the medium, these artists performed intimate events without audiences, often with a subversive or political overtone. Exhibited will be Szombathy’s iconic and rebellious work Bauhaus (1972/2013) performed in the attic he was renting in Novi Sad. The work portrays the humerous juxtaposition between his grim living conditions and his caustic political placards depicting the word BAUHAUS.

The unusual combination of neo-constructivism and conceptual art is best embodied in the works of Dóra Maurer and György Jovánovics. Included in the exhibition will be the work Sluices No. 9 (1980) by Maurer, an example of her experimental print making which also demonstrates her interest in the rigour of geometric abstraction. Maurer, whose work has finally received the deserved attention of the international art world was included in the recent exhibition Adventures of the Black Square at the Whitechapel Gallery, London and her 2014/2015 retrospective at Museum Ritter has highlighted the diversity of her highly regarded oeuvre.

Endre Tót, a key practitioner of Mail art, camouflaged his art in letterform in order to avoid the postal censorship of the time. Mail art was used as a common practice amongst the Eastern Bloc artists to disseminate their works and communicate with each other and their Western counterparts. In his series Zeropost, (1976) Tót mailed his letters with his Zero stamps as reflections of the absurdity of communication in a dictatorship. Ironically, despite the non-official postage, the letters still arrived at their destinations.

“Sending out a stamp, a letter or a card, something that in the west carried no risk and involved no emotional investment, was connected in the East with a defence of the basic human right to free expression and was often understood as a form of public service or protest.”[1]

As the art historian Piotr Piotrowski notes above, the context in which these works were made is crucial to their understanding. Hence whilst the artists behind the iron curtain were following current debates on contemporary art, they were not mimicking their achievements but only using Western practices as a point of reference. The members of the Hungarian unofficial art scene were keen to break the conventions of concrete art, fluxus, conceptual art and even pop art, as established in the West, by combining them in their unique visual language. What evolved was a radical new approach to conceptualism, underpinned by a highly political reaction to the denial of freedom in the practice of art.

Over the past three decades many exhibitions have explored and contextualised the neglected art movements of Eastern Europe. Among these shows, the following musems gave special attention to the Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde: Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s-1980s (1999, Queens Museum, New York), Aspekte/Positionen. 50 Jahre Kunst aus Mitteleuropa, 1949-1999 (1999, MUMOK, Vienna), and the Subversive Practices. Art under Conditions of Political Repression 60s–80s / South America / Europe (2009, Kunstverein, Stuttgart). Concurrently, both private and public collections began to acquire the works of these artists, including the Art Institute of Chicago, Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and Tate, London. In Vienna the Kontakt collection of the Erste Bank is dedicated solely to the post-war conceptual art scene of Eastern Europe

[1] Piotr Piotrowsky, In the Shadow of Yalta. Art and the Avant Garde in Eastern Europe 1945-1989 (London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2009)

Austin / Desmond Fine Art is delighted to announce an exhibition of works by the Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde in the first show of its kind to be held in London. Artists exhibited will include Gábor Attalai, Miklós Erdély, Tibor Hajas, György Jovánovics, Katalin Ladik, Dóra Maurer, Géza Perneczky, Endre Tót, Bálint Szombathy and Tamás Szentjóby.

In the post-war period Hungary suffered under the dictatorship of the Soviet Union whose ideology at the time was hostile to modern art. The authorities established the official art form of ‘Socialist Realism’, as representation of the achievements of the great socialist era. Parallel to this, Hungary’s artists were establishing what became known as the un-official art scene, working outside of the highly censored institutional system. This un-official scene often operated underground, using private apartments as show spaces and holding clandestine semi-illegal exhibitions. Their ‘isolation’ led to a flourishing alternative cultural milieu in which artists worked in intense interaction with each other regardless of the use of medium or artistic references.

Included in the exhibition at Austin / Desmond Fine Art will be works by nine of the leading protagonists of this movement. Miklós Erdély, one of the most important catalysts of the Hungarian un-official art scene and whose work Last Year’s Snow (1970)the exhibition title is taken from, will be exhibited alongside his renowned contemporary Tamás Szentjóby. Both artists reflect on the political and social issues of the time in a critical yet ironic way. St.Auby’s Fluxus objects include the Czechoslovak Radio (1968), an example of which was exhibited at Documenta in 2011: a simple painted brick alludes to the 1968 suppression of Czechoslovakia’s new reforms (Prague Spring) when citizens were banned from using radios and took to the streets with paper covered bricks in protest.

Also featured are the conceptual works of Gábor Attalai and Géza Perneczky alongside the photo-performance series by Bálint Szombathy, Katalin Ladik and Tibor Hajas. Using their bodies as the medium, these artists performed intimate events without audiences, often with a subversive or political overtone. Exhibited will be Szombathy’s iconic and rebellious work Bauhaus (1972/2013) performed in the attic he was renting in Novi Sad. The work portrays the humerous juxtaposition between his grim living conditions and his caustic political placards depicting the word BAUHAUS.

The unusual combination of neo-constructivism and conceptual art is best embodied in the works of Dóra Maurer and György Jovánovics. Included in the exhibition will be the work Sluices No. 9 (1980) by Maurer, an example of her experimental print making which also demonstrates her interest in the rigour of geometric abstraction. Maurer, whose work has finally received the deserved attention of the international art world was included in the recent exhibition Adventures of the Black Square at the Whitechapel Gallery, London and her 2014/2015 retrospective at Museum Ritter has highlighted the diversity of her highly regarded oeuvre.

Endre Tót, a key practitioner of Mail art, camouflaged his art in letterform in order to avoid the postal censorship of the time. Mail art was used as a common practice amongst the Eastern Bloc artists to disseminate their works and communicate with each other and their Western counterparts. In his series Zeropost, (1976) Tót mailed his letters with his Zero stamps as reflections of the absurdity of communication in a dictatorship. Ironically, despite the non-official postage, the letters still arrived at their destinations.

“Sending out a stamp, a letter or a card, something that in the west carried no risk and involved no emotional investment, was connected in the East with a defence of the basic human right to free expression and was often understood as a form of public service or protest.”[1]

As the art historian Piotr Piotrowski notes above, the context in which these works were made is crucial to their understanding. Hence whilst the artists behind the iron curtain were following current debates on contemporary art, they were not mimicking their achievements but only using Western practices as a point of reference. The members of the Hungarian unofficial art scene were keen to break the conventions of concrete art, fluxus, conceptual art and even pop art, as established in the West, by combining them in their unique visual language. What evolved was a radical new approach to conceptualism, underpinned by a highly political reaction to the denial of freedom in the practice of art.

Over the past three decades many exhibitions have explored and contextualised the neglected art movements of Eastern Europe. Among these shows, the following musems gave special attention to the Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde: Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s-1980s (1999, Queens Museum, New York), Aspekte/Positionen. 50 Jahre Kunst aus Mitteleuropa, 1949-1999 (1999, MUMOK, Vienna), and the Subversive Practices. Art under Conditions of Political Repression 60s–80s / South America / Europe (2009, Kunstverein, Stuttgart). Concurrently, both private and public collections began to acquire the works of these artists, including the Art Institute of Chicago, Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and Tate, London. In Vienna the Kontakt collection of the Erste Bank is dedicated solely to the post-war conceptual art scene of Eastern Europe

[1] Piotr Piotrowsky, In the Shadow of Yalta. Art and the Avant Garde in Eastern Europe 1945-1989 (London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2009)

Austin / Desmond Fine Art is delighted to announce an exhibition of works by the Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde in the first show of its kind to be held in London. Artists exhibited will include Gábor Attalai, Miklós Erdély, Tibor Hajas, György Jovánovics, Katalin Ladik, Dóra Maurer, Géza Perneczky, Endre Tót, Bálint Szombathy and Tamás Szentjóby.

In the post-war period Hungary suffered under the dictatorship of the Soviet Union whose ideology at the time was hostile to modern art. The authorities established the official art form of ‘Socialist Realism’, as representation of the achievements of the great socialist era. Parallel to this, Hungary’s artists were establishing what became known as the un-official art scene, working outside of the highly censored institutional system. This un-official scene often operated underground, using private apartments as show spaces and holding clandestine semi-illegal exhibitions. Their ‘isolation’ led to a flourishing alternative cultural milieu in which artists worked in intense interaction with each other regardless of the use of medium or artistic references.

Included in the exhibition at Austin / Desmond Fine Art will be works by nine of the leading protagonists of this movement. Miklós Erdély, one of the most important catalysts of the Hungarian un-official art scene and whose work Last Year’s Snow (1970)the exhibition title is taken from, will be exhibited alongside his renowned contemporary Tamás Szentjóby. Both artists reflect on the political and social issues of the time in a critical yet ironic way. St.Auby’s Fluxus objects include the Czechoslovak Radio (1968), an example of which was exhibited at Documenta in 2011: a simple painted brick alludes to the 1968 suppression of Czechoslovakia’s new reforms (Prague Spring) when citizens were banned from using radios and took to the streets with paper covered bricks in protest.

Also featured are the conceptual works of Gábor Attalai and Géza Perneczky alongside the photo-performance series by Bálint Szombathy, Katalin Ladik and Tibor Hajas. Using their bodies as the medium, these artists performed intimate events without audiences, often with a subversive or political overtone. Exhibited will be Szombathy’s iconic and rebellious work Bauhaus (1972/2013) performed in the attic he was renting in Novi Sad. The work portrays the humerous juxtaposition between his grim living conditions and his caustic political placards depicting the word BAUHAUS.

The unusual combination of neo-constructivism and conceptual art is best embodied in the works of Dóra Maurer and György Jovánovics. Included in the exhibition will be the work Sluices No. 9 (1980) by Maurer, an example of her experimental print making which also demonstrates her interest in the rigour of geometric abstraction. Maurer, whose work has finally received the deserved attention of the international art world was included in the recent exhibition Adventures of the Black Square at the Whitechapel Gallery, London and her 2014/2015 retrospective at Museum Ritter has highlighted the diversity of her highly regarded oeuvre.

Endre Tót, a key practitioner of Mail art, camouflaged his art in letterform in order to avoid the postal censorship of the time. Mail art was used as a common practice amongst the Eastern Bloc artists to disseminate their works and communicate with each other and their Western counterparts. In his series Zeropost, (1976) Tót mailed his letters with his Zero stamps as reflections of the absurdity of communication in a dictatorship. Ironically, despite the non-official postage, the letters still arrived at their destinations.

“Sending out a stamp, a letter or a card, something that in the west carried no risk and involved no emotional investment, was connected in the East with a defence of the basic human right to free expression and was often understood as a form of public service or protest.”[1]

As the art historian Piotr Piotrowski notes above, the context in which these works were made is crucial to their understanding. Hence whilst the artists behind the iron curtain were following current debates on contemporary art, they were not mimicking their achievements but only using Western practices as a point of reference. The members of the Hungarian unofficial art scene were keen to break the conventions of concrete art, fluxus, conceptual art and even pop art, as established in the West, by combining them in their unique visual language. What evolved was a radical new approach to conceptualism, underpinned by a highly political reaction to the denial of freedom in the practice of art.

Over the past three decades many exhibitions have explored and contextualised the neglected art movements of Eastern Europe. Among these shows, the following musems gave special attention to the Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde: Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s-1980s (1999, Queens Museum, New York), Aspekte/Positionen. 50 Jahre Kunst aus Mitteleuropa, 1949-1999 (1999, MUMOK, Vienna), and the Subversive Practices. Art under Conditions of Political Repression 60s–80s / South America / Europe (2009, Kunstverein, Stuttgart). Concurrently, both private and public collections began to acquire the works of these artists, including the Art Institute of Chicago, Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and Tate, London. In Vienna the Kontakt collection of the Erste Bank is dedicated solely to the post-war conceptual art scene of Eastern Europe

Including works by:

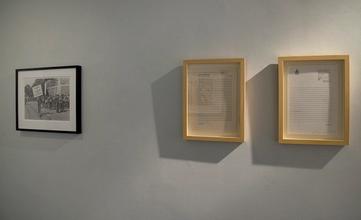

Installation Shots , Gábor Attalai, Miklós Erdély, Tibor Hajas, György Jovánovics, Katalin Ladik, Dóra Maurer, Géza Perneczky, Tamás Szentjóby, Bálint Szombathy, Endre Tót